This contrasts with pooled mortality of 21% (95%CI: 17-26%, 17 studies) from controlled trial settings. Pooled short-term mortality (defined as ≤2 weeks or in-hospital) for cryptococcal meningitis under routine care settings was 44% (95%CI: 39-49%, 40 studies) with no difference in mortality when stratified by treatment (amphotericin vs. In the fourth study (Chapter 5), I describe results from a systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating published mortality estimates for common HIV-associated meningitides in sub-Saharan Africa, under routine care conditions and “clinical trial” settings subject to more intensive clinical management. ≤20 cells/µL) was not a predictor of mortality in the setting of advanced immune-deficiency (median CD4 136 cells/µL). For HIV-associated cases without a cause identified, CSF inflammation (CSF WCC >20 cells/µL vs.

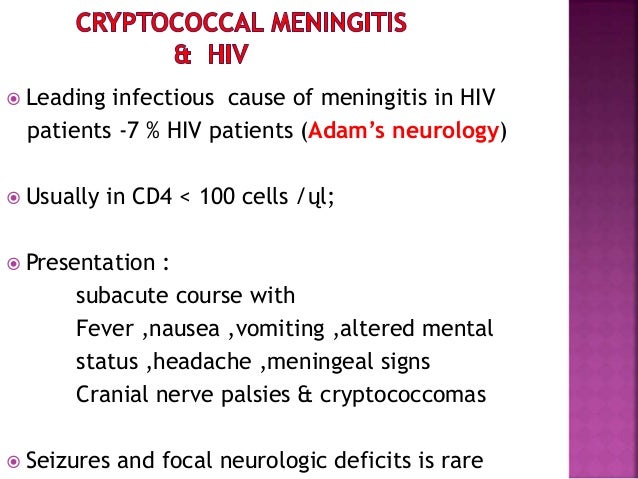

One-year mortality for culture-negative, pneumococcal, and TB meningitis were 49%, 49%, and 56%, respectively. Missed doses of amphotericin were common and independently predicted poor outcomes, while adherence to interventions usually associated with improved outcomes such as therapeutic lumbar punctures was poor. Estimated mortality for cryptococcal meningitis under routine care settings in Botswana was 50% at 10 weeks and 65% at one year with amphotericin B-based therapy, similar to mortality estimated in sub-Saharan Africa with less potent fluconazole therapy. This was done deterministic linkage of CSF to vital status records in a national death registry with a unique national identification number (“Omang”). In the third study (Chapter 4), I evaluated outcomes of “culture-positive” (including cryptococcal, pneumococcal, or TB) and culture-negative suspected meningitis (stratified by CSF white cell count ) in a retrospective cohort study. Incidence was two-fold higher in HIV-positive men than women. Using UNAIDS population data, we estimated a 2013-2014 national cryptococcal meningitis incidence of 17.8 cases / 100,000 person-years (PYO), or 96.8 cases / 100,000 PYO in HIV-positive, nearly identical to estimates from Gauteng Province, South Africa in the pre-ART era of 2002-2004.

Most evaluations for meningitis were in individuals with known HIV (73%), almost half (47%) of these with a preceding history of ART use. Other causes of meningitis were rarely identified. Forty-one percent (8759/21,560) of cases of suspected meningitis in adults had abnormal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings, half of these receiving a diagnosis of cryptococcal meningitis. In the first two studies (Chapters 2-3), I discuss results from the Botswana National Meningitis Survey, a 16-year national cross-sectional audit of patients evaluated for meningitis by lumbar puncture with CSF analysis from 2000-2015, including complete national records for 20. Finally, I discuss estimates of the impact and cost-effectiveness of preventing cryptococcal meningitis – the most common cause of meningitis we observed in Botswana – through cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) screening and targeted pre-emptive antifungal therapy for individuals with advanced HIV. I compare local findings in Botswana to other settings in sub-Saharan Africa through a systematic review and meta-analysis. Linking cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) laboratory records of patients evaluated with meningitis to HIV and vital status records from national electronic registries, I provide novel insights into HIV correlates and outcomes from suspected and microbiologically-confirmed meningitis. In this dissertation, I discuss results from research conducted in Botswana, a country in southern Africa with an HIV prevalence that is among the highest in the world, including the first comprehensive meningitis national incidence estimates in a high HIV prevalence country and temporal trends over 16 years with national scale-up of ART. Central nervous system infection are a primary cause of HIV-associated morbidity and mortality worldwide.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)